From Leeds to Eranos: The Hidden Path of Spirit in Modern Art

Alfred Orage, Herbert Read and Luigi Pericle: Genealogies of a Spiritual Vision

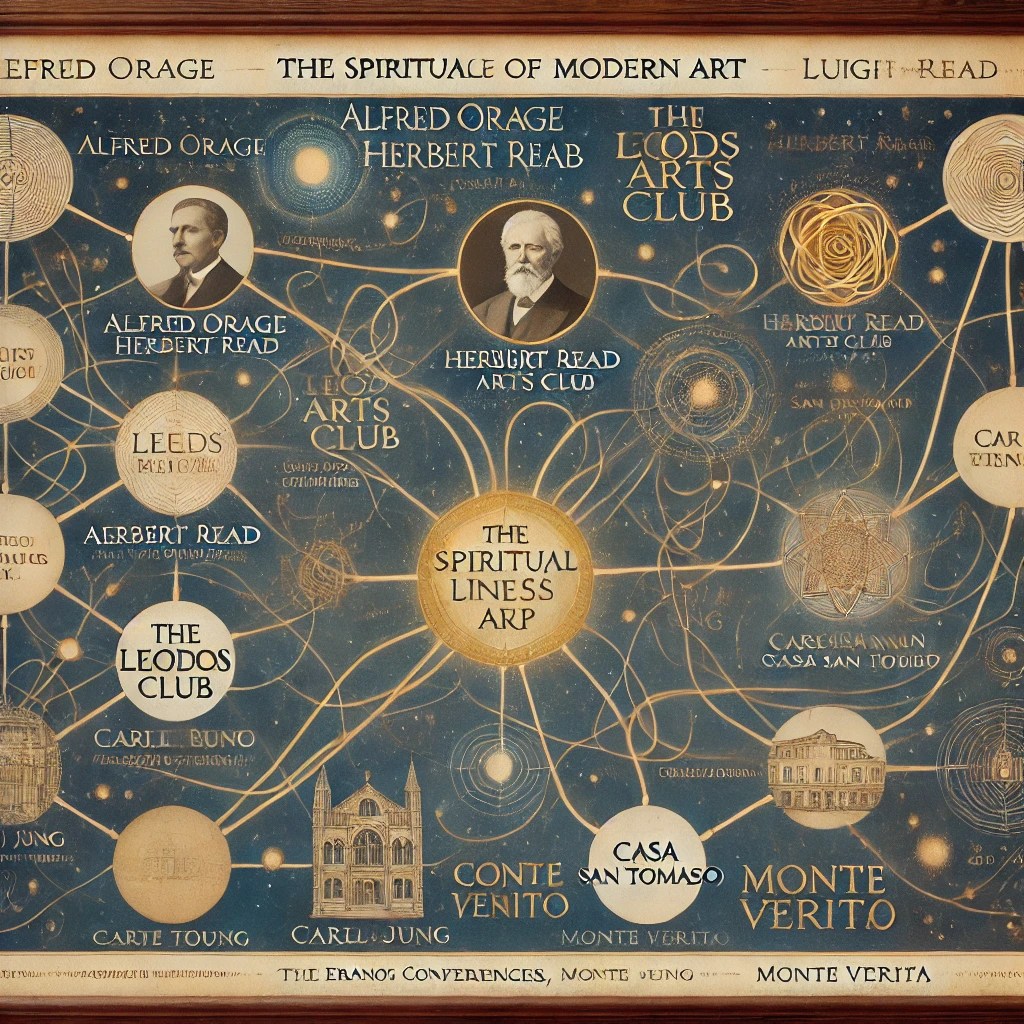

At the dawn of the 20th century, in the industrial heart of northern England, something remarkable took shape among the smoke of factories and the silence of esoteric libraries. In Leeds, in 1903, a young thinker and teacher named Alfred Richard Orage founded a cultural circle that would become legendary: the Leeds Arts Club.

More than a simple salon, the Club was a philosophical and spiritual crossroads, welcoming theosophy, symbolism, Nietzschean aesthetics, and the stirrings of a modern mysticism. Unsurprisingly, it met in the halls of the Theosophical Society in Leeds. There, the thought of Edward Carpenter, Gurdjieff, Swedenborg, and Bergson mixed freely with discussions on modern art, political utopia, and Eastern philosophy.

In this vibrant and highly spiritual environment, the young Herbert Read (1893–1968) — poet, critic, and future theorist of modern art — was formed. It was here that Read first encountered the idea that art is not a mere craft or ornament, but a vehicle for transcendent experience, a mirror of the invisible. That early intuition would become the guiding principle of his entire life’s work.

Herbert Read: The Critic as Initiate

Herbert Read would later become one of the first Western art critics to consciously and openly embrace the spiritual dimension of modern art. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not fear the irrational or the symbolic — for Read, art was neither propaganda nor a social product, but a biological and psychic event, an archetypal expression of the soul.

He was a strong advocate of Kandinsky, Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, and others, and was one of the earliest British intellectuals to engage seriously with the thought of Carl Gustav Jung. Read would go on to become co-editor of the English edition of Jung’s Collected Works, alongside Michael Fordham and Gerhard Adler.

His seminal book The Meaning of Art (1931) is still essential for understanding art as a universal symbolic language. In Education Through Art (1943), Read argued that artistic experience could actually save the individual from neurosis, serving as a therapeutic path to harmony:

“Every child is an artist; it is society, not nature, that represses creativity.”

From “Club” to “Conference”: Read at Eranos

In the 1950s, Read’s intellectual and spiritual journey reached its natural culmination in the Swiss setting of Eranos, the fabled conference cycle founded in 1933 by Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn in Ascona, at the foot of Monte Verità — a hill already rich in spiritual experiments and theosophical communities, anarchist colonies, and pacifist visions.

Between 1953 and 1964, Read participated in several Eranos conferences, sharing the stage with thinkers such as Mircea Eliade, Henry Corbin, D.T. Suzuki, Gershom Scholem, and Jung himself. He brought with him the conviction that modern art — from sculpture to abstraction — was a new language of the eternal, a medium for the sacred.

It was probably during one of his stays in Ascona that Read visited the studio of the enigmatic artist and mystic Luigi Pericle.

Luigi Pericle: The Hermit Painter

Luigi Pericle Giovannetti (1916–2001), painter, writer, illustrator and mystic, lived just above Lake Maggiore in the now-iconic Casa San Tomaso, a stone’s throw from the Eranos Foundation. After enjoying international acclaim in the 1950s and early 60s — with his drawings published by Penguin and Macmillan, and his paintings exhibited alongside Dubuffet and Tàpies — Pericle abruptly and voluntarily withdrew from the art world in 1965.

Choosing a life of solitude, Pericle devoted himself to a deep inner path: study, astrology, esoteric philosophy, painting — always painting. His work became increasingly abstract, visionary, and silent.

Herbert Read, upon visiting his studio, was struck by the artist’s quiet genius. He wrote:

“I found an artist whose work immediately impressed me by its professional skill and strange beauty. Here was clearly an artist who had perfected his talent in stillness, and used it to express a subtle perception of reality […] a long pursuit of an absolute beauty.”

This testimony — now part of the book Luigi Pericle: A Rediscovery — sealed a rare artistic and spiritual kinship. Read saw in Pericle what he had always searched for: an artist-seer, someone for whom painting was not technique, but transmission.

The Mystical Triangle: Orage – Read – Pericle

The arc that connects Orage, Read, and Pericle is more than a biography. It forms a spiritual lineage in the modern age: from the early symbolist-modernist ferment in Leeds, to Read’s theorization of art as inner transformation, to Pericle’s hermitic creation of a visionary, alchemical art of silence.

This triad invites us to rethink modern art history not as a sequence of styles, but as a spiritual journey — a secret path of initiation, traced through image and symbol, through matter and imagination.

As Pericle wrote in one of his unpublished notes:

“Art is not representation. It is revelation.”

In a time obsessed with visibility, these thinkers remind us of the power of the invisible — and of the responsibility of art to remain faithful to it.

Dall’ Leeds Arts Club a Eranos: la via segreta dello spirito nell’arte moderna

Alfred Orage, Herbert Read e Luigi Pericle: genealogie di una visione spirituale

All’inizio del Novecento, nel cuore pulsante dell’Inghilterra industriale, qualcosa di straordinario prese forma tra i fumi delle fabbriche e i silenzi delle biblioteche esoteriche. A Leeds, nel 1903, un giovane pensatore e insegnante di nome Alfred Richard Orage fondò un cenacolo destinato a diventare leggendario: il Leeds Arts Club.

Più che un semplice circolo culturale, il Club era un crocevia filosofico e spirituale, aperto al pensiero simbolista, alle istanze della teosofia, all’estetica nietzscheana, e agli echi di una mistica moderna. Non a caso, le sue prime sedi furono ospitate all’interno della Società Teosofica di Leeds. Qui si discuteva di Edward Carpenter, di Gurdjieff, di Swedenborg, ma anche di arte contemporanea, politica socialista, psicologia, e filosofia orientale.

In questo ambiente intensamente vivo, spirituale e intellettualmente fertile, si formò Herbert Read (1893–1968), figura chiave del pensiero artistico europeo del Novecento. Il giovane Read — allora poco più che un poeta reduce dalla Prima guerra mondiale — entrò in contatto con l’idea che l’arte potesse e dovesse essere un veicolo per l’esperienza del sacro, un ponte tra il visibile e l’invisibile. Un’intuizione che sarebbe diventata la stella polare del suo pensiero.

Herbert Read: il critico come iniziato

Read divenne nel tempo uno dei primi critici a riconoscere con consapevolezza e profondità il ruolo dello spirituale nell’arte moderna. A differenza di molti suoi contemporanei, non temeva il simbolico, l’esoterico, l’intuizione. Per lui l’arte non era un semplice prodotto sociale, ma un fenomeno biologico e psichico, una manifestazione archetipica dell’essere.

Sostenitore di Kandinsky, Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Read fu anche uno dei primi intellettuali britannici ad avvicinarsi al pensiero di Carl Gustav Jung, di cui fu co-editore delle Opere complete in inglese, assieme a Gerhard Adler e Michael Fordham.

Il suo capolavoro teorico, The Meaning of Art (1931), è ancora oggi uno dei testi fondamentali per comprendere l’arte come linguaggio simbolico universale. In Education Through Art (1943), invece, Read arriva a sostenere che l’esperienza artistica sia un processo salvifico, capace di armonizzare l’essere umano, salvandolo dalla nevrosi. Scrive:

“Ogni bambino è un artista; è la società, non la natura, a reprimere la sua creatività.”

Dal “Club” al “Convegno”: Read a Eranos

Negli anni Cinquanta, il percorso di Read trovò un punto di approdo naturale nel contesto svizzero di Eranos, il mitico ciclo di conferenze fondato nel 1933 da Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn ad Ascona, ai piedi del Monte Verità — luogo già impregnato da decenni di esperienze teosofiche, anarchiche, pacifiste e utopiche.

Read partecipò ai simposi di Eranos tra il 1953 e il 1964, condividendo la scena con Mircea Eliade, Henry Corbin, Suzuki, Gershom Scholem e Jung stesso. Il suo contributo non fu solo estetico: fu esistenziale. A Eranos, Read portò la consapevolezza che l’arte moderna — dalla scultura astratta alla pittura informale — non fosse altro che un nuovo linguaggio per l’eterno, per l’ineffabile.

E non è un caso che proprio ad Ascona, in quello stesso contesto spirituale e culturale, Herbert Read incontrò Luigi Pericle.

Luigi Pericle: l’artista eremita

Luigi Pericle Giovannetti (1916–2001), pittore, scrittore, illustratore e iniziato, visse a pochi passi dal Monte Verità, in quella Casa San Tomaso che ancora oggi custodisce il suo lascito. Dopo un successo internazionale come artista e autore — i suoi disegni furono pubblicati da Penguin e Macmillan, e le sue opere esposte in Inghilterra accanto a quelle di Dubuffet e Tàpies — nel 1965, al culmine della carriera, Pericle si ritirò volontariamente dal mondo, per dedicarsi a una vita di studio, meditazione e pittura.

Quando Herbert Read visitò il suo studio, ne rimase profondamente colpito. Scrisse:

“Trovai un artista il cui lavoro mi impressionò subito per la padronanza tecnica e la bellezza singolare. Era evidente che quest’artista aveva perfezionato il proprio talento nel silenzio, usandolo per esprimere una percezione sottile della realtà. […] Una lunga ricerca della bellezza assoluta.”

Questa testimonianza – riportata nel volume Luigi Pericle: A Rediscovery – sigilla un legame spirituale ed estetico profondo. Read aveva riconosciuto in Pericle un artista “iniziato”, affine a quelli di cui aveva sempre parlato: un “pittore della coscienza”.

Il triangolo mistico: Orage – Read – Pericle

L’arco che unisce Orage, Read e Pericle non è solo biografico. È un filo rosso spirituale che attraversa il Novecento: dalla nascita del pensiero simbolico-moderno a Leeds, alla teorizzazione dell’arte come strumento di trasformazione, fino alla realizzazione silenziosa di un’arte sacra, esoterica e visionaria nella pittura di Pericle.

Questa genealogia ci invita a rileggere la storia dell’arte moderna da una prospettiva interiore: non più come sequenza di stili e movimenti, ma come via di conoscenza, come percorso iniziatico, come ascesi creativa.

Come ha scritto Pericle, in una delle sue pagine manoscritte:

“L’arte non è decorazione, è evocazione. Non rappresenta la realtà: la rivela.”

E se c’è un’eredità che oggi possiamo (e dobbiamo) riscoprire, è proprio questa: quella di un’arte che non ha paura del mistero, che guarda dentro anziché fuori, e che resta fedele all’invisibile, anche quando il mondo vuole solo il visibile.